La logique du langage probabiliste

Dans ce chapitre, nous aborderons la logique du langage couplée aux probabilités mathématiques. Nous avons vu que logique classique à elle seule ne suffit pas à déterminer des diagnostics précis; par conséquent, un aperçu conceptuel et formel est donné sur les raisons pour lesquelles la probabilité peut être très utile. En fournissant des illustrations d'exemples de cas cliniques, nous verrons comment la logique du langage probabiliste est capable de nous fournir un diagnostic différentiel de manière « assez bonne »..

La conclusion est qu'il est possible de démontrer que, même avec l'ajout du seul raisonnement probabiliste, il n'est pas possible de déterminer des diagnostics exacts, donc d'autres enrichissements sont recherchés pour notre langage.

Logique probabiliste du langage en médecine

Chaque idée scientifique (que ce soit en médecine, en architecture, en ingénierie, en chimie ou dans tout autre domaine), lorsqu'elle est mise en pratique, est sujette à de petites erreurs et incertitudes. Les mathématiques - à travers la théorie des probabilités et l'inférence statistique - aident à contrôler avec précision et ainsi contenir ces incertitudes. Il faut toujours considérer que dans tous les cas pratiques "les résultats dépendent également de nombreux autres facteurs externes à la théorie", qu'il s'agisse de conditions initiales et environnementales, d'erreurs expérimentales ou d'autre chose..

Toutes les incertitudes sur ces facteurs font de la relation théorie-observation une relation probabiliste. Dans l'approche médicale, il existe deux types d'incertitudes qui pèsent le plus sur les diagnostics : l'incertitude subjective et la fatalité..[1][2]

Il devient donc essentiel dans ce scénario de distinguer ces deux incertitudes et de montrer que la notion de probabilité a des sens différents dans ces deux contextes.

Nous tenterons d'exposer ces concepts en reliant chaque étape cruciale à l'approche clinique qui a été rapportée dans les chapitres précédents et en particulier l'approche dans le contexte dentaire et neurologique en luttant pour la primauté du diagnostic pour notre chère Mary Poppins.

Incertitude subjective et pertes

Imaginons de demander à Mary Poppins lequel des deux collègues médecins – le dentiste ou le neurologue – a raison.

La question créerait une sorte d'agitation fondée sur l'incertitude intérieure ; par conséquent, les notions de certitude et d'incertitude se réfèrent à des états épistémiques subjectifs des êtres humains et non à des états du monde extérieur, car il n'y a ni certitude ni incertitude dans ce monde. En ce sens, comme nous l'avons mentionné, il existe un monde intérieur et un monde extérieur à nous-mêmes qui, tous deux, ne répondent pas aux canons de l'incertitude, mais de la probabilité.

Mary Poppins peut être subjectivement certaine ou incertaine quant à savoir si elle souffre de TTM ou d'une forme neuropathique ou neuromusculaire d'OP : ceci parce que « l'incertitude » est un état épistémique subjectif en dessous du seuil de la connaissance et de la croyance ; d'où le terme.

Incertitude subjective

Sans aucun doute, le terme « subjectif » effraie beaucoup, en particulier ceux qui ont l'intention de pratiquer la science en poursuivant l'idéal sain d'« objectivité », tel que ce terme est perçu par le bon sens. Il convient donc d'apporter quelques précisions sur l'utilisation de ce terme dans ce contexte:

- ‘Subjectif’ indique que l'évaluation de la probabilité dépend du statut d'information de la personne qui l'effectue.

- ‘Subjectif’ ne veut pas dire arbitraire.

La soi-disant « objectivité », telle que perçue par les personnes extérieures à la recherche scientifique, est définie lorsqu'une communauté d'êtres rationnels partage le même état d'information. Mais même dans ce cas, il faudrait plutôt parler d'« intersubjectivité » (c'est-à-dire le partage, par un groupe, d'opinions subjectives)

Dans les cas cliniques — précisément parce que les patients possèdent rarement des notions avancées de médecine — l'incertitude subjective doit être prise en compte. Vivre dans l'incertitude nous oblige à utiliser une approche probabiliste.

Accidentée

L'accident indique l'absence d'un certain lien entre la cause et l'effet. L'incertitude d'une union étroite entre la source et le phénomène est l'un des problèmes les plus défavorables dans la détermination d'un diagnostic.

Dans un cas clinique un phénomène (comme par exemple une malocclusion, une occlusion croisée, une béance, etc...) est aléatoirement associé à un autre phénomène (comme la dégénérescence osseuse de l'ATM); quand il y a des exceptions pour lesquelles la proposition logique ce n'est pas toujours vrai (mais c'est la plupart du temps), on dira que la relation n'est pas toujours vrai mais c'est probable.

Probabilité subjective et objective

Dans ce chapitre, quelques sujets déjà traités dans le livre fantastique de Kazem Sadegh-Zadeh[3], qui aborde le problème de la logique du langage médical, sont repris et nous reformulons leur contenu en les renvoyant à notre cas clinique de Mary Poppins, pour garder notre compréhension au plus près des contextes dentaires.

Des événements aléatoires et subjectivement incertains sont dits probables ; par conséquent, les accidents et l'incertitude sont traités comme des probabilités qualitatives, comparatives ou quantitatives.

Pour clarifier ce concept, reprenons l'exemple de Mary Poppins. Un médecin, ayant entendu ses symptômes pourra dire que :

- Mary Poppins souffre probablement de TMD (terme qualitatif).

- Mary Poppins est plus susceptible d'avoir des TMD que l'OP neuropathique (terme comparatif: nombre de cas diagnostiqués de TMD par rapport à nOP.

- La probabilité que Mary Poppins ait des TMD est de 0,15 (terme quantitatif, relatif à la population).

Probabilité subjective

Dans un contexte d'incertitude subjective humaine, les données probabilistes, qualitatives, comparatives et/ou quantitatives peuvent être interprétées comme une mesure d'incertitude subjective par le clinicien, afin de rendre les « états de conviction » numériquement représentables.

Par exemple, dire que « la probabilité que Mary Poppins soit affectée par les TMD est de 0,15 des cas » revient à dire « dans la mesure de 15 %, je pense que Mary Poppins est affectée par les TMD » ; ce qui signifie que le degré de conviction est le degré de probabilité subjective.

Probabilité objective

D'autre part, les événements et les processus aléatoires ne peuvent pas être décrits par des processus déterministes sous la forme « si A alors B ». Les statistiques sont utilisées pour quantifier la fréquence d'association entre A et B et pour représenter les relations entre eux comme un degré de probabilité qui introduit le degré de probabilité objective.

Dans le sillage de la probabilité croissante de l'incertitude et de l'aléatoire en médecine depuis le XVIIIe siècle, le terme « probabilité » est devenu un élément respecté du langage médical, de la méthodologie et de l'épistémologie.

Malheureusement, les deux types de probabilité, la probabilité subjective et la probabilité objective, ne sont pas différenciées avec précision en médecine, et il en va de même dans d'autres disciplines. Le fait fondamental reste que le sens le plus important que la théorie des probabilités a généré en médecine, en particulier dans les concepts de probabilité en étiologie, épidémiologie, diagnostic et thérapie, est sa contribution à notre compréhension et représentation de l'accident biologique.

Analyse probabiliste-causale

De ces prémisses, il est clair que le diagnostic clinique est fait en utilisant la méthode dite hypothétique-déductive appelée DN[4] (deductive-nomological model[5]). Mais ce n'est pas réaliste, car les connaissances médicales utilisées dans la prise de décision clinique contiennent à peine des lois déterministes causales pour permettre des explications causales et, par conséquent, pour formuler des diagnostics cliniques, entre autres dans le contexte spécialisé. Essayons d'analyser à nouveau le cas de notre Mary Poppins, en essayant cette fois une approche probabiliste-causale.

Considérons un certain nombre d'individus, y compris les personnes qui signalent une douleur bucco-faciale qui ont généralement une dégénérescence osseuse de l'articulation temporo-mandibulaire. Cependant, il peut également y avoir d'autres causes apparemment sans rapport. Nous devons traduire mathématiquement la « pertinence » que ces incertitudes causales ont pour déterminer un diagnostic.

La pertinence occasionnelle

Pour ce faire nous considérons le degré de pertinence causale d'un événement par rapport à un événement où :

- = patients atteints de dégénérescence osseuse de l'articulation temporo-mandibulaire.

- = patients signalant une douleur orofaciale.

- = patients sans dégénérescence osseuse de l'articulation temporo-mandibulaire.

Nous utiliserons la probabilité conditionnelle , c'est-à-dire la probabilité que l'événement ne se produise qu'après que l'événement ait déjà eu lieu.

Avec ces prémisses, la pertinence causale de l'échantillon de patients est :

où

- indique la probabilité que certaines personnes (parmi les pris en considération) souffrent de douleur oro-faciale causée par une dégénérescence osseuse de l'articulation temporo-mandibulaire,

tandis que

- indique la probabilité que d'autres personnes (toujours parmi les pris en considération) souffrent de douleur orofaciale conditionnée par autre chose que la dégénérescence osseuse de l'articulation temporo-mandibulaire.

Puisque toute probabilité suggère que est une valeur comprise entre et , le paramètre sera un nombre compris entre et .

Les significations que l'on peut donner à ce nombre sont les suivantes :

- nous avons les cas extrêmes (qui en réalité ne se produisent jamais) qui sont :

- indiquant que la seule cause de douleur orofaciale est la dégénérescence osseuse de l'ATM,

- ce qui indique que la cause de la douleur orofaciale n'est jamais la dégénérescence osseuse de l'ATM mais est autre chose,

- indiquant que la probabilité que la douleur orofaciale soit causée par une dégénérescence osseuse de l'ATM ou autrement est exactement la même,

- et les cas intermédiaires (qui sont les réalistes)

- indiquant que la cause de la douleur bucco-faciale est plus susceptible d'être une dégénérescence osseuse de l'ATM,

- ce qui indique que la cause de la douleur orofaciale n'est probablement pas une dégénérescence osseuse de l'ATM.

Deuxième approche clinique

(survolez les images)

So be it then the probability of finding, in the sample of our people, individuals who present the elements belonging to the aforementioned set

In order to take advantage of the information provided by this dataset, the concept of partition of causal relevance is introduced:

The partition of causal relevance

- Always be the number of people we have to conduct the analyses upon, if we divide (based on certain conditions as explained below) this group into subsets with , a cluster is created that is called a "partition set" :

where with the symbolism it indicates that the subclass is contained in .

The partition , in order for it to be defined as a partition of causal relevance, must have these properties:

- For each subclass the condition must apply ie the probability of finding in the subgroup a person who has the symptoms, clinical signs and elements belonging to the set . A causally relevant partition of this type is said to be homogeneous.

- Each subset must be 'elementary', i.e. it must not be further divided into other subsets, because if these existed they would have no causal relevance.

Now let us assume, for example, that the population sample , to which our good patient Mary Poppins belongs, is a category of subjects aged 20 to 70. We also assume that in this population we have those who present the elements belonging to the data set which correspond to the laboratory tests mentioned above and precisa in 'The logic of classical language'.

Let us suppose that in a sample of 10,000 subjects from 20 to 70 we will have an incidence of 30 subjects showing clinical signs and . We preferred to use these reports for the demonstration of the probabilistic process because in the literature the data regarding clinical signs and symptoms for Temporomandibular Disorders have too wide a variation as well as too high an incidence in our opinion.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

An example of a partition with presumed probability in which TMJ degeneration (Deg.TMJ) occurs in conjunction with Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) would be the following:

| where | |||||

| where | |||||

| where | |||||

| where |

Clinical situations

These conditional probabilities demonstrate that each of the partition's four subclasses is causally relevant to patient data in the population sample . Given the aforementioned partition of the reference class, we have the following clinical situations:

- Mary Poppins degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins degeneration of the temporomandibular joint no Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins no degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins no degeneration of the temporomandibular joint no Temporomandibular Disorders

To arrive at the final diagnosis above, we conducted a probabilistic-causal analysis of Mary Poppins' health status whose initial data were .

In general, we can refer to a logical process in which we examine the following elements:

- an individual:

- its initial data set

- a population sample to which it belongs,

- a base probability

At this point we should introduce too specialized arguments that would take the reader off the topic but that have an high epistemic importance for which we will try to extract the most described logical thread of the Analysandum/Analysans concept.

The probabilistic-causal analysis of is then a couple of the following logical forms (Analysandum / Analysans[12]):

- Analysandum : is a logical form that contains two parameters: probability to select a person who has the symptoms and elements belonging to the set , and the generic individual who is prone to those symptoms.

- Analysan : is a logical form that contains three parameters: the partition , the generic individual belonging to the population sample and (Knowledge Base) which includes a set of statements of conditioned probability.

For example, it can be concluded that the definitive diagnosis is the following:

- this means that our Mary Poppins is 95% affected by TMDs, since she has a degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint in addition to the positive data

Final considerations

We took a long and tortuous path to better understand the complexity encountered by the colleague struggling with the very heavy ethical responsibility of making a diagnosis. However, this task becomes even more complex when we need to be detailed and careful in making a differential diagnosis.

Here, we enter a delicate topic, that is connected with the epistemological contents and that first of all was reported in the "Introduction". We are talking about:

- Interdisciplinarity:

In science policy, it is generally recognized that science-based problem solving requires interdisciplinary research (IDR), as proposed by the EU project called Horizon 2020[13]. In a recent study, the authors focus on the question why researchers have cognitive and epistemic difficulties in conducting IDR. It is believed that the loss of philosophical interest in the epistemology of interdisciplinary research is caused by a philosophical paradigm of science called "Physics Paradigm of Science", which prevents recognition of important IDR changes in both the philosophy of science and research.

The proposed alternative philosophical paradigm, called 'Engineering Paradigm of Science', makes alternative philosophical assumptions about aspects such as the purpose of science, the character of knowledge, the epistemic and pragmatic criteria for the acceptance of knowledge and the role of technological tools. Consequently, scientific researchers need so-called metacognitive scaffolds to assist them in the analysis and reconstruction of how 'knowledge' is constructed in different disciplines.

In interdisciplinary research, metacognitive scaffolds help interdisciplinary communication analyse and articulate how the discipline builds knowledge[14][15]

This concept is linked to the previously discussed topic in which the colleague should be aware of his own 'Subjective Uncertainty' (due to a classic logic language 'sick or healthy') and of 'Objective Uncertainty' (due to a probabilistic logic language 'probably sick or probably healthy'). It is not complicated to prove this assertion: the uncertainty we are talking about derives from the fact that the elements, assertions, data, classes and subclasses mentioned and that build the apparatus of the logic of probabilistic's language: Analysandum and Analysan are elements that exist in a specific world, and in this case in a dental context in which the element of the process indisputably indicates a "basic knowledge" only in a specific dental context.

This conclusion confirmed by the dentist was the following:

or better: it is my 95% belief that Mary Poppins is affected by TMDs since she has a degeneration of the temporomandibular joint in addition to the positivity of the data

But something strange happens because out of nowhere, a researcher, who uses 'metacognitive scaffolds'[16] for an implementation in the analysis and reconstruction of how 'knowledge' is built in different disciplines, demands an answer to the following question from the dentist:

and increase the dose: submit Mary Poppins to the following trigeminal electrophysiological tests, label them as we did previously for the set data generating another set containing a number of unknown data (not belonging to the purely dental branch) thereby creating an entirely new set that we will call (called precisely due to the presence of data unknown to the dental context).

Positive radiological report of the TMJ in Figure 2

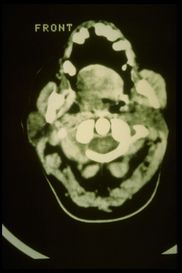

Positive CT report of the TMJ in Figure 3

Positive axiographic report of the condylar traces in Figure 4

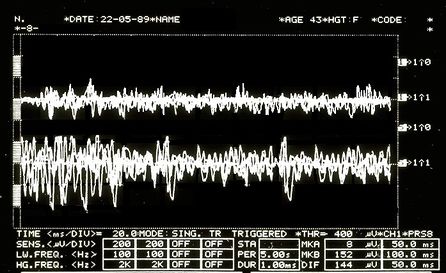

Asymmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5

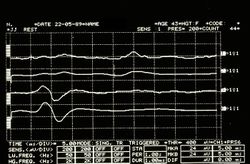

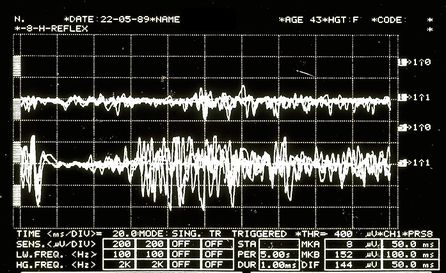

Jaw jerk in Figure 6

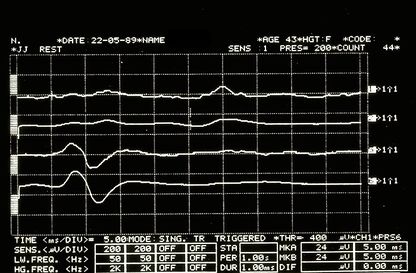

Mechanical Silent Period in Figure 7

CT right masseter muscle in Figure 8

Third Clinical Approach

(hover over the images)

In this way it has been shown that, inevitably,

By exploring this perimeter line of the specialist context, we will create an area close to it which we will call the 'fuzzy zone' or 'fuzzy logic' which we will discuss in the next chapter.

(in fact, for this reason we should also consider Fuzzy Logic Language)

- ↑ Vázquez-Delgado E, Cascos-Romero J, Gay-Escoda C, «Myofascial pain associated to trigger points: a literature review. Part 2: differential diagnosis and treatment», in Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 2007.

PMID:20173729

DOI:10.4317/medoral.15.e639 - ↑ Thoppay J, Desai B, «Oral burning: local and systemic connection for a patient-centric approach», in EPMA J, 2019.

PMID:30984309 - PMCID:PMC6459460

DOI:10.1007/s13167-018-0157-3 - ↑ Sadegh-Zadeh Kazem, «Handbook of Analytic Philosophy of Medicine», Springer, 2012, Dordrecht.

ISBN: 978-94-007-2259-0

DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-2260-6 . - ↑ Sarkar S, «Nagel on Reduction», in Stud Hist Philos Sci, 2015.

PMID:26386529

DOI:10.1016/j.shpsa.2015.05.006 - ↑ Modèle DN d'explication scientifique, aussi connu sous le nom Le modèle de Hempel, Hempel–Oppenheim model, Popper–Hempel model, ou modèle de loi couvrant

- ↑ Pantoja LLQ, De Toledo IP, Pupo YM, Porporatti AL, De Luca Canto G, Zwir LF, Guerra ENS, «Prevalence of degenerative joint disease of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review», in Clin Oral Investig, 2019.

PMID:30311063

DOI:10.1007/s00784-018-2664-y - ↑ De Toledo IP, Stefani FM, Porporatti AL, Mezzomo LA, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G, «Prevalence of otologic signs and symptoms in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis», in Clin Oral Investig, 2017.

PMID:27511214

DOI:10.1007/s00784-016-1926-9 - ↑ Bonotto D, Penteado CA, Namba EL, Cunali PA, Rached RN, Azevedo-Alanis LR, «Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in rugby players», in Gen Dent.

PMID:31355769 - ↑ da Silva CG, Pachêco-Pereira C, Porporatti AL, Savi MG, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G, «Prevalence of clinical signs of intra-articular temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis», in Am Dent Assoc, 2016. - PMCID:26552334

DOI:10.1016/j.adaj.2015.07.017 - ↑ Gauer RL, Semidey MJ, «Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders», in Am Fam Physician, 2015.

PMID:25822556 - ↑ Kohlmann T, «Epidemiology of orofacial pain», in Schmerz, 2002.

PMID:12235497

DOI:10.1007/s004820200000 - ↑ Westmeyer H, «The diagnostic process as a statistical-causal analysis», in APA, 1975.

DOI:10.1007/BF00139821

This is an Open Access resource - ↑ European Union, Horizon 2020

- ↑ Boon M, Van Baalen S, «Epistemology for interdisciplinary research - shifting philosophical paradigms of science», in Eur J Philos Sci, 2019.

DOI:10.1007/s13194-018-0242-4 9(1):16. - ↑ Boon M, «An engineering paradigm in the biomedical sciences: Knowledge as epistemic tool», in Prog Biophys Mol Biol, 2017.

DOI:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2017.04.001 - ↑ Boon M, Van Baalen S, «Epistemology for interdisciplinary research - shifting philosophical paradigms of science», in Eur J Philos Sci, 2019.

PMID:30873248 - PMCID:PMC6383598

DOI:10.1007/s13194-018-0242-4

This is an Open Access resource

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system