La lógica del lenguaje probabilístico

En este capítulo, discutiremos la lógica del lenguaje junto con la probabilidad matemática.. Hemos visto que lógica clásica por sí sola es insuficiente para determinar diagnósticos precisos; por lo tanto, se ofrece una descripción general conceptual y formal de por qué la probabilidad puede ser muy útil.. Incluyendo ilustraciones de casos de casos clínicos, veremos cómo la lógica del lenguaje probabilístico es capaz de proporcionarnos un diagnóstico diferencial de una manera "suficientemente buena"..

La conclusión es que es posible demostrar que, incluso con la sola adición del razonamiento probabilístico, no es posible determinar diagnósticos exactos, por lo que se buscan otros enriquecimientos para nuestro lenguaje..

Lógica probabilística del lenguaje en medicina

Toda idea científica (ya sea en medicina, arquitectura, ingeniería, química o cualquier otra materia), cuando se pone en práctica, está sujeta a pequeños errores e incertidumbres.. Las matemáticas, a través de la teoría de la probabilidad y la inferencia estadística, ayudan a controlar con precisión y, por lo tanto, a contener estas incertidumbres.. Siempre hay que tener en cuenta que en todos los casos prácticos "los resultados también dependen de muchos otros factores externos a la teoría", ya sean condiciones iniciales y ambientales, errores experimentales u otra cosa..

Todas las incertidumbres sobre estos factores hacen que la relación teoría-observación sea probabilística. En el enfoque médico, hay dos tipos de incertidumbre que más pesan en los diagnósticos: la incertidumbre subjetiva y la casualidad..[1][2]

Por lo tanto, en este escenario resulta esencial distinguir entre estas dos incertidumbres y mostrar que el concepto de probabilidad tiene significados diferentes en estos dos contextos..

Intentaremos exponer estos conceptos vinculando cada paso crucial con el enfoque clínico que se ha informado en los capítulos anteriores y, en particular, el enfoque en el contexto dental y neurológico en la lucha por la primacía del diagnóstico para nuestra querida Mary Poppins..

Incertidumbre subjetiva y siniestro

Imaginemos preguntarle a Mary Poppins cuál de los dos colegas médicos - el dentista o el neurólogo - tiene razón..

La pregunta crearía una especie de agitación basada en la incertidumbre interior; por tanto, las nociones de certeza e incertidumbre se refieren a estados epistémicos subjetivos del ser humano y no a estados del mundo externo, porque no hay certeza ni incertidumbre en ese mundo. En este sentido, como hemos mencionado, hay un mundo interior y un mundo fuera de nosotros que ambos no responden a cánones de incertidumbre, pero sí de probabilidad.

Mary Poppins puede estar subjetivamente segura o insegura de si sufre de TMD o una forma neuropática o neuromuscular de OP: esto porque la "incertidumbre" es un estado epistémico subjetivo por debajo del umbral del conocimiento y la creencia; de ahí el término.

Incertidumbre subjetiva

Sin duda, el término "subjetivo" asusta a muchos, especialmente a aquellos que tienen la intención de practicar la ciencia persiguiendo el ideal saludable de la "objetividad", como este término es percibido por el sentido común. Por tanto, conviene hacer algunas aclaraciones sobre el uso de este término en este contexto.:

- ‘Subjetivo’ indica que la evaluación de la probabilidad depende del estado de la información de la persona que la realiza.

- ‘Subjetivo’ No significa arbitrario.

La llamada "objetividad", tal como la perciben quienes están fuera de la investigación científica, se define cuando una comunidad de seres racionales comparte el mismo estado de información. Pero incluso en este caso, se debería hablar más propiamente de "intersubjetividad" (es decir, el intercambio, por un grupo, de opiniones subjetivas).

En los casos clínicos - precisamente porque los pacientes rara vez poseen nociones avanzadas de medicina - debe tenerse en cuenta la incertidumbre subjetiva. Vivir con incertidumbre requiere que usemos un enfoque probabilístico.

Casualidad

La casualidad indica la falta de una cierta conexión entre causa y efecto. La incertidumbre de una estrecha unión entre la fuente y el fenómeno es uno de los problemas más adversos para determinar un diagnóstico.

En un caso clínico, un fenómeno (como por ejemplo una maloclusión, una mordida cruzada, una mordida abierta, etc.) se asocia aleatoriamente con otro fenómeno Failed to parse (syntax error): {\displaystyle B (x) < / math> (como la degeneración ósea de la ATM); cuando hay excepciones para las cuales la proposición lógica <math> A (x) \ rightarrow B (x) } no siempre es cierta (pero lo es la mayor parte del tiempo), diremos que la relación no siempre es cierto pero es probable.

Probabilidad subjetiva y objetiva

En este capítulo, algunos temas ya tratados en el fantástico libro de Kazem Sadegh-Zadeh[3], quienes abordan el problema de la lógica del lenguaje médico, son retomados y remodelamos su contenido remitiéndolos a nuestro caso clínico de Mary Poppins, para acercar nuestra comprensión a los contextos dentales.

Se dice que los sucesos aleatorios y subjetivamente inciertos son probables; en consecuencia, la casualidad y la incertidumbre se tratan como probabilidades cualitativas, comparativas o cuantitativas.

Para aclarar este concepto, volvamos al ejemplo de Mary Poppins. Un médico, habiendo escuchado sus síntomas, podrá decir que:

- Mary Poppins probablemente sufre de TMD (término cualitativo).

- Mary Poppins is more likely to have TMDs than neuropathic OP (comparative term: number of diagnosed cases of TMDs versus nOP.

- The probability that Mary Poppins has TMDs is 0.15 (quantitative term, relative to the population).

Subjective probability

In a context of human subjective uncertainty, the probabilistic, qualitative, comparative and/or quantitative data can be interpreted as a measure of subjective uncertainty by the clinician, in order to make the 'states of conviction' numerically representable.

For example, saying that "the probability that Mary Poppins is affected by TMDs is 0.15 of the cases" is the same as saying "in the measure of 15%, I believe that Mary Poppins is affected by TMDs"; which means that the degree of conviction is the degree of subjective probability.

Objective probability

On the other hand, events and random processes cannot be described by deterministic processes in the form 'if A then B'. Statistics are used to quantify the frequency of association between A and B and to represent the relationships between them as a degree of probability that introduces the degree of objective probability.

In the wake of the growing probabilization of uncertainty and randomness in medicine since the eighteenth century, the term "probability" has become a respected element of medical language, methodology and epistemology.

Unfortunately, the two types of probability, the subjective probability and the objective one, are not accurately differentiated in medicine, and the same happens in other disciplines too. The fundamental fact remains that the most important meaning that probability theory has generated in medicine, particularly in the concepts of probability in aetiology, epidemiology, diagnostics and therapy, is its contribution to our understanding and representation of biological casuality.

Probabilistic-causal analysis

From these premises it is clear that the clinical diagnosis is made using the so-called hypothetical-deductive method referred to as DN[4] (deductive-nomological model[5]). But this is not realistic, since the medical knowledge used in clinical decision-making hardly contains causal deterministic laws to allow causal explanations and, hence, to formulate clinical diagnoses, among other things in the specialist context. Let us try to analyse again the case of our Mary Poppins, this time trying a probabilistic-causal approach.

Let us consider a number of individuals including people who report Orofacial Pain who generally have bone degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint. However, there may also be other apparently unrelated causes. We must mathematically translate the 'relevance' that these causal uncertainties have in determining a diagnosis.

The casual relevance

To do this we consider the degree of causal relevance of an event with respect to an event where:

- = patients with bone degeneration of the temporomandibular joint.

- = patients reporting orofacial pain.

- = patients without bone degeneration of the temporomandibular joint.

We will use the conditional probability , that is the probability that the event occurs only after the event has already occurred.

With these premises the causal relevance of the sample of patients is:

where

- indicates the probability that some people (among taken into consideration) suffer from Orofacial Pain caused by bone degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint,

while

- indicates the probability that other people (always among taken into consideration) suffer from Orofacial Pain conditioned by something other than bone degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint.

Since all probability suggest that is a value between and , the parameter will be a number that is between and .

The meanings that we can give to this number are as follows:

- we have the extreme cases (which in reality never occur) which are:

- indicating that the only cause of orofacial pain is bone degeneration of the TMJ,

- which indicates that the cause of orofacial pain is never bone degeneration of the TMJ but is something else,

- indicating that the probability that orofacial pain is caused by bone degeneration of the TMJ or otherwise is exactly the same,

- and the intermediate cases (which are the realistic ones)

- indicating that the cause of orofacial pain is more likely to be bone degeneration of the TMJ,

- which indicates that the cause of orofacial pain is more likely not bone degeneration of the TMJ.

Second Clinical Approach

(hover over the images)

So be it then the probability of finding, in the sample of our people, individuals who present the elements belonging to the aforementioned set

In order to take advantage of the information provided by this dataset, the concept of partition of causal relevance is introduced:

The partition of causal relevance

- Always be the number of people we have to conduct the analyses upon, if we divide (based on certain conditions as explained below) this group into subsets with , a cluster is created that is called a "partition set" :

where with the symbolism it indicates that the subclass is contained in .

The partition , in order for it to be defined as a partition of causal relevance, must have these properties:

- For each subclass the condition must apply ie the probability of finding in the subgroup a person who has the symptoms, clinical signs and elements belonging to the set . A causally relevant partition of this type is said to be homogeneous.

- Each subset must be 'elementary', i.e. it must not be further divided into other subsets, because if these existed they would have no causal relevance.

Now let us assume, for example, that the population sample , to which our good patient Mary Poppins belongs, is a category of subjects aged 20 to 70. We also assume that in this population we have those who present the elements belonging to the data set which correspond to the laboratory tests mentioned above and precisa in 'The logic of classical language'.

Let us suppose that in a sample of 10,000 subjects from 20 to 70 we will have an incidence of 30 subjects showing clinical signs and . We preferred to use these reports for the demonstration of the probabilistic process because in the literature the data regarding clinical signs and symptoms for Temporomandibular Disorders have too wide a variation as well as too high an incidence in our opinion.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

An example of a partition with presumed probability in which TMJ degeneration (Deg.TMJ) occurs in conjunction with Temporomandibular Disorders (TMDs) would be the following:

| where | |||||

| where | |||||

| where | |||||

| where |

Clinical situations

These conditional probabilities demonstrate that each of the partition's four subclasses is causally relevant to patient data in the population sample . Given the aforementioned partition of the reference class, we have the following clinical situations:

- Mary Poppins degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins degeneration of the temporomandibular joint no Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins no degeneration of the temporomandibular joint Temporomandibular Disorders

- Mary Poppins no degeneration of the temporomandibular joint no Temporomandibular Disorders

To arrive at the final diagnosis above, we conducted a probabilistic-causal analysis of Mary Poppins' health status whose initial data were .

In general, we can refer to a logical process in which we examine the following elements:

- an individual:

- its initial data set

- a population sample to which it belongs,

- a base probability

At this point we should introduce too specialized arguments that would take the reader off the topic but that have an high epistemic importance for which we will try to extract the most described logical thread of the Analysandum/Analysans concept.

The probabilistic-causal analysis of is then a couple of the following logical forms (Analysandum / Analysans[12]):

- Analysandum : is a logical form that contains two parameters: probability to select a person who has the symptoms and elements belonging to the set , and the generic individual who is prone to those symptoms.

- Analysan : is a logical form that contains three parameters: the partition , the generic individual belonging to the population sample and (Knowledge Base) which includes a set of statements of conditioned probability.

For example, it can be concluded that the definitive diagnosis is the following:

- this means that our Mary Poppins is 95% affected by TMDs, since she has a degeneration of the Temporomandibular Joint in addition to the positive data

Final considerations

We took a long and tortuous path to better understand the complexity encountered by the colleague struggling with the very heavy ethical responsibility of making a diagnosis. However, this task becomes even more complex when we need to be detailed and careful in making a differential diagnosis.

Here, we enter a delicate topic, that is connected with the epistemological contents and that first of all was reported in the "Introduction". We are talking about:

- Interdisciplinarity:

In science policy, it is generally recognized that science-based problem solving requires interdisciplinary research (IDR), as proposed by the EU project called Horizon 2020[13]. In a recent study, the authors focus on the question why researchers have cognitive and epistemic difficulties in conducting IDR. It is believed that the loss of philosophical interest in the epistemology of interdisciplinary research is caused by a philosophical paradigm of science called "Physics Paradigm of Science", which prevents recognition of important IDR changes in both the philosophy of science and research.

The proposed alternative philosophical paradigm, called 'Engineering Paradigm of Science', makes alternative philosophical assumptions about aspects such as the purpose of science, the character of knowledge, the epistemic and pragmatic criteria for the acceptance of knowledge and the role of technological tools. Consequently, scientific researchers need so-called metacognitive scaffolds to assist them in the analysis and reconstruction of how 'knowledge' is constructed in different disciplines.

In interdisciplinary research, metacognitive scaffolds help interdisciplinary communication analyse and articulate how the discipline builds knowledge[14][15]

This concept is linked to the previously discussed topic in which the colleague should be aware of his own 'Subjective Uncertainty' (due to a classic logic language 'sick or healthy') and of 'Objective Uncertainty' (due to a probabilistic logic language 'probably sick or probably healthy'). It is not complicated to prove this assertion: the uncertainty we are talking about derives from the fact that the elements, assertions, data, classes and subclasses mentioned and that build the apparatus of the logic of probabilistic's language: Analysandum and Analysan are elements that exist in a specific world, and in this case in a dental context in which the element of the process indisputably indicates a "basic knowledge" only in a specific dental context.

This conclusion confirmed by the dentist was the following:

or better: it is my 95% belief that Mary Poppins is affected by TMDs since she has a degeneration of the temporomandibular joint in addition to the positivity of the data

But something strange happens because out of nowhere, a researcher, who uses 'metacognitive scaffolds'[16] for an implementation in the analysis and reconstruction of how 'knowledge' is built in different disciplines, demands an answer to the following question from the dentist:

and increase the dose: submit Mary Poppins to the following trigeminal electrophysiological tests, label them as we did previously for the set data generating another set containing a number of unknown data (not belonging to the purely dental branch) thereby creating an entirely new set that we will call (called precisely due to the presence of data unknown to the dental context).

Positive radiological report of the TMJ in Figure 2

Positive CT report of the TMJ in Figure 3

Positive axiographic report of the condylar traces in Figure 4

Asymmetric EMG interference pattern in Figure 5

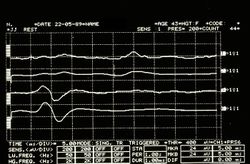

Jaw jerk in Figure 6

Mechanical Silent Period in Figure 7

CT right masseter muscle in Figure 8

Third Clinical Approach

(hover over the images)

In this way it has been shown that, inevitably,

By exploring this perimeter line of the specialist context, we will create an area close to it which we will call the 'fuzzy zone' or 'fuzzy logic' which we will discuss in the next chapter.

(in fact, for this reason we should also consider Fuzzy Logic Language)

- ↑ Vázquez-Delgado E, Cascos-Romero J, Gay-Escoda C, «Myofascial pain associated to trigger points: a literature review. Part 2: differential diagnosis and treatment», in Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 2007.

PMID:20173729

DOI:10.4317/medoral.15.e639 - ↑ Thoppay J, Desai B, «Oral burning: local and systemic connection for a patient-centric approach», in EPMA J, 2019.

PMID:30984309 - PMCID:PMC6459460

DOI:10.1007/s13167-018-0157-3 - ↑ Sadegh-Zadeh Kazem, «Handbook of Analytic Philosophy of Medicine», Springer, 2012, Dordrecht.

ISBN: 978-94-007-2259-0

DOI:10.1007/978-94-007-2260-6 . - ↑ Sarkar S, «Nagel on Reduction», in Stud Hist Philos Sci, 2015.

PMID:26386529

DOI:10.1016/j.shpsa.2015.05.006 - ↑ DN model of scientific explanation, also known as Hempel's model, Hempel–Oppenheim model, Popper–Hempel model, or covering law model

- ↑ Pantoja LLQ, De Toledo IP, Pupo YM, Porporatti AL, De Luca Canto G, Zwir LF, Guerra ENS, «Prevalence of degenerative joint disease of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review», in Clin Oral Investig, 2019.

PMID:30311063

DOI:10.1007/s00784-018-2664-y - ↑ De Toledo IP, Stefani FM, Porporatti AL, Mezzomo LA, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G, «Prevalence of otologic signs and symptoms in adult patients with temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis», in Clin Oral Investig, 2017.

PMID:27511214

DOI:10.1007/s00784-016-1926-9 - ↑ Bonotto D, Penteado CA, Namba EL, Cunali PA, Rached RN, Azevedo-Alanis LR, «Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in rugby players», in Gen Dent.

PMID:31355769 - ↑ da Silva CG, Pachêco-Pereira C, Porporatti AL, Savi MG, Peres MA, Flores-Mir C, De Luca Canto G, «Prevalence of clinical signs of intra-articular temporomandibular disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis», in Am Dent Assoc, 2016. - PMCID:26552334

DOI:10.1016/j.adaj.2015.07.017 - ↑ Gauer RL, Semidey MJ, «Diagnosis and treatment of temporomandibular disorders», in Am Fam Physician, 2015.

PMID:25822556 - ↑ Kohlmann T, «Epidemiology of orofacial pain», in Schmerz, 2002.

PMID:12235497

DOI:10.1007/s004820200000 - ↑ Westmeyer H, «The diagnostic process as a statistical-causal analysis», in APA, 1975.

DOI:10.1007/BF00139821

This is an Open Access resource - ↑ European Union, Horizon 2020

- ↑ Boon M, Van Baalen S, «Epistemology for interdisciplinary research - shifting philosophical paradigms of science», in Eur J Philos Sci, 2019.

DOI:10.1007/s13194-018-0242-4 9(1):16. - ↑ Boon M, «An engineering paradigm in the biomedical sciences: Knowledge as epistemic tool», in Prog Biophys Mol Biol, 2017.

DOI:10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2017.04.001 - ↑ Boon M, Van Baalen S, «Epistemology for interdisciplinary research - shifting philosophical paradigms of science», in Eur J Philos Sci, 2019.

PMID:30873248 - PMCID:PMC6383598

DOI:10.1007/s13194-018-0242-4

This is an Open Access resource

particularly focusing on the field of the neurophysiology of the masticatory system